Only Connect is quite a good motto for this blog as we are seeing London in bite sized chunks and every so often there is a connection with somewhere or something else.

Now today if people know the phrase they probably associate “Only Connect” with a fiendishly difficult panel game programme on BBC4 hosted by Victoria Coren Mitchell. But the phrase itself was originally used as the epigraph to E. M. Forster’s 1910 novel Howards End. And why have I chosen this phrase for W4 as opposed to any other postcode? Well E M Forster lived for over 20 years in W4 as we shall see.

We start our walk at Chiswick Post Office, 1 Heathfield Terrace, just off of Chiswick High Road. Turn right out of the Post Office and almost immediately you are in Barley Mow Passage.

Stop 1: Voysey House

Our first stop is just a little way along Barley Mow Passage on the left past the Lamb Brewery. It is a white tiled building which turns out to be by Charles Voysey, best known for his country houses and for his Arts and Crafts wallpaper, fabrics and furnishing designs. This was his only factory building, according to architectural historian Pevsner.

This building dates from 1902 and was built as an extension to Sanderson’s wallpaper factory which was opposite. It is faced with white tiles with black bandings. Apparently these were originally blue brick but at some stage they were painted black. If only all factories were this lovely! The building was restored in 1989 and is now offices, fittingly called Voysey House.

Retrace you steps back to the Post Office and then keep walking along Heathfield Terrace. Our next stop is on the left.

Stop 2: Chiswick Town Hall

This italianate building looks to me a bit like a railway station but it was Chiswick’s Town Hall. The central section dates from 1876 but the three bays on the left in our picture and the one bay to the right were added in 1900. Apparently it has well preserved interiors.

Chiswick was first an urban district but after merger with neighbouring Brentford in 1927, it became a municipal borough in 1932. This then became part of the new London Borough of Hounslow which was created in 1965. These buildings are still used by the borough council, although the main civic centre is in Hounslow.

Immediately opposite the Town Hall is Town Hall Avenue – such originality in the naming of this street. Go down this and just past the church at the end turn left into Chiswick High Road. A little way along on the left is Sutton Lane North. Go down this a short way. Our next stop is the first block on the right hand side of the road.

Stop 3: Arlington Park Mansions

Across the road is a fairly ordinary looking block of mansion flats dating from around 1900.

The reason we are pausing here though is because this was where Edward Morgan (E M) Forster lived for over 20 years from 1939. There is a blue plaque.

E M Forster only published 5 novels in his lifetime – four between 1905 (Where Angels fear to tread) and 1910 (Howards End) and a fifth (A Passage to India) in 1924. A sixth novel, Maurice, was only published after his death. No doubt this was because it is a gay love story, and that was why it came out later, so to speak. Although there were no more finished novels, he did produce some short stories and some non fiction writing, and he broadcast on the radio. And with Eric Crozier, he wrote the libretto for Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd in 1951.

Only Connect as I mentioned was the epigraph for Howards End. An epigraph by the way is a phrase, quotation, or poem at the beginning. It can be a preface, a summary or a link to some other work. In Howards End it is kind of the first two of these. And it has been said that “only connect” is applicable not just to practically all his work but to E M Forster himself.

Forster had a long standing relationship with a younger man called Bob Buckingham but he was also on friendly terms with Buckingham’s wife and was godfather to their son. There is a fascinating article from the Guardian about this.

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/feb/17/e-m-forster-my-policeman

Now return to Chiswick High Road and cross over and go down the road opposite, past the entrance to Sainsbury’s

Stop 4: Chiswick Park Station

Ahead you can hardly fail to miss Chiswick Park station.

The first station here was opened in 1879 by the Metropolitan District Railway on its extension from Turnham Green to Ealing Broadway. Initially it was called Acton Green which is nearby to the east. It was renamed Chiswick Park and Acton Green in 1889. Finally it became known as Chiswick Park in 1910. The station was rebuilt between 1931 and 1932, in preparation for the western extension of the Piccadilly Line from Hammersmith. However this was to provide the extra tracks for the Piccadilly Line but only platforms were provided for the District line at this station.

The new station was designed by Charles Holden in a modern European style using brick, reinforced concrete and glass. Apparently this was inspired by Krumme Lanke station in Berlin. But it is odd to have gone to the trouble of building such a significant building when it is only served by Ealing Broadway District line trains, the Richmond trains pass close by and of course the Piccadilly line has no platforms.

The platforms with their concrete canopies are well preserved and there are some interesting original signs.

Now retrace your steps to Chiswick High Road and turn left. Our next stop is a short distance along the High Road, on the left.

Stop 5: 414 Chiswick High Road (site of Chiswick Empire Theatre)

There is a modern parade of shop, all mostly empty and above at Number 414 is a dumpy glass office block. This was the site of the Chiswick Empire Theatre.

The theatre opened in September 1912. Apparently it took promoter Oswald Stoll over a year to gain planning permission as the locals thought that a music hall or variety theatre was not an appropriate form of entertainment for Chiswick. This building was designed by renown theatre architect Frank Matcham. The exterior was neo-classical style with a two storey centrally placed opening, which contained an open verandah. The auditorium seated almost 2,000.

Chiswick Empire was not just a twice nightly variety theatres, it also hosted revues, plays and even the occasional opera. As happened in so many other places the audiences declined after the Second World War and the theatre was eventually closed in 1959. But it went out with a bang. The final shows in June 1959 were sell outs by the flamboyant American entertainer Liberace. Now all we have is this rather boring (and disused) office block in its place.

Continue walking alomg Chiswick High Road and take a right into Dukes Avenue (There is a catholic church on the corner). Continue to the end of this street. Ahead at the end is the Great West Road, but to cross this we need to use the subway which is the continuation of the left hand pavement. On the other side, take the right hand passage, and follow the signs for Chiswick House.

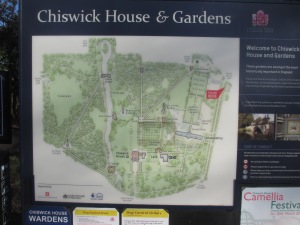

You cannot miss the gates to the grounds of Chiswick House. This is a fabulous Palladian Mansion, now managed by English Heritage. However the House opens only from April to October and as it is now January, we cannot actually go inside. Maybe next time. But you can look down the lovely tree lined avenue or even go and view the outside of the House.

Follow the signs for Hogarth’s House along the main road and soon you will see a gate on the right.

Stop 6: Hogarth’s House

Artist, printer and engraver, William Hogarth lived and worked here for the last 15 years of this life. He is of course best known for his moralistic pictures, such as the Rake’s Progress, Marriage a la Mode and Beer Street and Gin Lane. Although some of these started out as paintings the reason they became so well known was that he also made engravings of them. So there were many copies in circulation.

He married Jane Thornhill, daughter of artist Sir James Thornhill in 1729. The Hogarths had no children, although they fostered foundling children. He was one of the first Governors of the Foundling Hospital which was set up in 1741 by the sea captain Thomas Coram. This was not a hospital in the medical sense. It was rather a place of hospitality, established for the education and maintenance of children who had been abandoned.

The Hogarths lived in Leicester Square (sadly their house no longer exists having been demolished in 1870) but they bought this building in 1749 as their country home. It now belongs to the London Borough of Hounslow and is open to visitors free of charge. It is well worth a look in. The only sad thing is the location which is right next to the A4 with its dual three lanes of constant traffic. Rather different from how it must have been in Hogarth’s time.

Go out of Hogarth’s House and turn right at the street. Ahead you will see the Hogarth roundabout and the flyover – often refered to in the traffic reports on local radio and television.

Beyond you can see the Fuller’s Brewery. Now if we had more time we would go down Church Street, to St Nicholas Church where Hogarth is buried and then go along the river for a bit. It is a beautiful spot here and hard to believe there is a working brewery in the midst of this. But sadly we have to be selective. However you can book a Brewery Tours if you are interested and there is even a virtual tour on the Fullers website: http://www.fullers.co.uk/rte.asp?id=98

So once across to the far side of the Hogarth roundabout you will see a pub.

Stop 7: Mawson Arms/Fox and Hounds

Have a closer look and you will see it has two names. First it says “The Fox and Hounds” and then “The Mawson Arms”

This is bacause once there were actually two pubs here but now there is just the one.

But turn the corner and you find there is a blue plaque.

Alexander Pope (1688 – 1744) was an 18th century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. Apparently he is the third most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson.

Just in front of the Mawson Arms is another subway. Go under this and you will come out by Chiswick Lane. Go along this road with the playing field on your right. At the end of this street is Chiswick High Road. Turn right here and cross over. Our next stop is a little way down on the left hand side as you are walking.

Stop 8: 70 Chiswick High Road

There is a sign over the entrance to No 70 Chiswick High Road which proclaims “The Power House”.

The reason is simple. The brick building just behind here was a power station built for the London United Electrical Tramway Company in 1899-1901. These were the days before the national grid and electricity had to be generated close to where it was needed. As architectural historian Pevsener puts it “The Chiswick building is the best surviving example in London from the early heroic era of generating stations whose bulky intrusions in residential areas was tempered by thoughtful architectural treatment.”

So we have a vast Baroque brick box with stone trimmings. You cannot really see that much from the street but walk a little along to the next side street (Merton Avenue). Look down there and you will see how this building looms over its surroundings.

And here was also a tram depot here. This is now become Stamford Brook bus garage, which fittingly is home to buses operated by the London United bus company – but as we saw with London General in SW15 and SW19 this is a modern day resurrection and today’s company has no direct link to the original company. By the way, London United is owned by RATP which operates the metro and bus system in Paris!

Retrace your steps along Chiswick High Road. Our next stop is on the same side of the road as the Power House

Stop 9: 160 Chiswick High Road (“The Old Cinema”)

This was originally built in 1887 as a ballroom and function room called the Chiswick Hall. It converted to become the Royal Cinema Electric Theatre in May 1912 and it survived as a cinema until around 1933 or 1934.

By 1939 it was a furniture store known as Chiswick Furniture Galleries. Since the mid 1980s it has been an antique shop known as ‘The Old Cinema’. Whilst it has been changed to work as a shop, you can just about see the skeleton of the old cinema lurking here and there – both in the internal structure of the building and its decorative features.

Continue along the High Road. Note the modern statue of Hogarth across the road just as we reach the junction of Turnham Green Terrace.

Turn right down Turnham Green Terrace. I should just mention in passing, this street has a number of nice looking food shops. There are two delis, a cake shop, a fishmongers and a butchers – the latter had people queueing out the door.

Stop 10: Chiswick Back Common/Acton Green

Just before the railway bridge, there is a green on the left. This is Chiswick Back Common.

Have a look at the display board to the left of the name board.

This explains that hereabouts was fought one of the major battles of the English Civil War. This was the Battle of Turnham Green which occurred on 13 November 1642.

On the battlefield, there was a standoff between the Royalists and the Parliamentarians. By successfully blocking the Royalist army’s way to London, the Parliamentarians gained an important strategic victory. The King and his army to retreat to Oxford for secure winter quarters. This was as close as the Royalists would get to London and without control of London they could never win. As far as I can discover there is not actually anything to see apart from this display board but I thought it was still worth a mention.

Now continue under the railway bridge. On our left the open space is called “Acton Green Common” which must have been a bit confusing. As we have heard Chiswick Park station was originally called Acton Green and yet Acton Green Common is actually almost outside Turnham Green station

So far so confusing. But Turnham Green is the open space by the High Road where the Town Hall is and where the Empire Theatre used to be. So here you have it. Turnham Green Station is actually by Acton Green and the station that used to be Acton Green is actually the nearest station to the open space called Turnham Green. These railway companies have a lot to answer for.

Stop 11: Bedford Park – St Mary’s Church and Tabard Inn

Just after the station, ahead of us is the early garden suburb of Bedford Park. Bedford Park was a speculative development by a man called Jonathan Carr. And what makes this so special is not only the green spaces and trees but the fact that the suburb takes the red brick and tile of a market town rather than classical, italianate or gothic styles. The importance of Bedford Park was recognised in 1967 when 356 Bedford Park buildings were Grade II listed and then in 1969 it became one of the first conservation areas.

We do not have time to explore fully the whole of Bedford Park. But we can just drop by two of its buildings, both designed by Norman Shaw, who was estate architect from 1877 – 1880 and then a consultant until 1886.

The road running off to the right is Bath Road and just on the corner ahead is St Michael and All Angels Church. This has a really wonderful interior. But the outside on Bath Road (shown in picture) looks very unchurchlike. It seems more like a church hall or school.

Poet, Sir John Betjeman described St Michael’s as “a very lovely church and a fine example of Norman Shaw’s work.” He said that Shaw had written in a letter to an architect friend saying: “I’m a house man – not a church man – and soil pipes are my speciality.” Nevertheless this is a fine church.

Then opposite the church (on the same side as the railway) is the Tabard Inn, dating from 1880. The current inn (it does not seem right to call it a mere pub) incorporates the Bedford Park Stores, which was a shop built for the new estate.

Keep walking along Bath Road.

Stop 12: 62 Bath Road

Our final stop (the house at Number 62) is on the right, just before a green and the boundary between Hounslow and Hammersmith & Fulham. But I guess we are still technically in Bedford Park.

This is the house where artist Lucien Pissarro lived with his family for a few years from 1897. Between 7 May and 20 July 1897, his father Camille stayed there while Lucien was convalescing from a stroke. Camille had been in London before, most notably in the 1870s when he stayed in Norwood.

When he was at Bath Road he painted a number of pictures locally, one of which is owned by the Ashmolean in Oxford. It is called Bath Road, London and includes his daughter in law Esther and grand daughter Orovida playing in the front garden. It is unfinished, unfortunately. But here’s a link anyway:

In 1902, Lucien and his family moved a short distance to 27 Stamford Brook Road and there is a blue plaque to him there. Although this is just down the road, we are not going there because it is over the border in W6!

So this brings us to the end of the W4 walk. It has been a full assortment taking in a writer, a couple of artists, the sites of a civil war battle, a theatre and a cinema, plus an early power station. And it was not just the latter we could only connect to.

From here there are buses to Shepherd’s Bush and beyond. Or else you can go down the next side street from where there is a pathway to Stamford Brook station. Alternatively you can retrace your steps to Turnham Green station.